Opinion

#EndSARS: Rage Of The Deprived ‘Phone-Pressing’ Generation

By Joel Nwokeoma

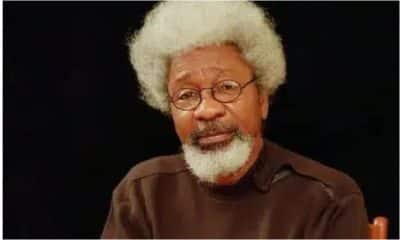

In 1984, Nobel laureate, Wole Soyinka, described his generation as a “wasted” one. His contention was that they were not able to salvage the country and put it on the path of national prosperity as envisaged at independence even with all the opportunities at their disposal. Like a magistrate, the literary icon thundered: “After a quarter of a century of witnessing and occasionally participating in varied aspects of social struggle in all their shifting tempi, dimensions, pragmatic and sometimes even ideologically oriented goals, I feel at this moment that I can only describe my generation as the wasted generation, frustrated by forces which are readily recognisable, which can be understood and analysed but which nevertheless have succeeded in defying whatever weapons such ‘understanding’ has been able to muster towards their defeats.”

More than three decades later, this time in 2012, political economist, Prof Pat Utomi, was no less poetic, calling his own as “the generation that left town.” He lamented that “the men who ran Nigeria 40 years ago as 20 and 30 something-year-olds without the benefits of the education (Sir Eric) Ashby felt so proud of, still run Nigeria as 70-something-year-olds and still call those 10 years younger, young men, just as they did 40 years ago…The truth for me is that my generation which enjoyed that high quality education found there was little space to add the value it could, and in the main, walked. They are the champions of the brain drain.”

Utomi said members of his generation, brimming with lofty dreams and innovative ideas, but lacking the “space” to deploy them, frustratingly “left the country to positions in Europe and North America.” To his credit, however, Utomi was humble enough to concede that, “My generation… was not responsible for the mess because it left town, but it probably deserves blame as good, if not worse, for not having the character to challenge and stop the rot.”

The rot not stopped then has since mutated into a scourge, or an albatross sadly so, which the ruling class had better address expertly in their enlightened self-interest. Interestingly, both the “wasted generation” and the “generation that left town” enjoyed the best of the young Nigeria nation-state, in terms of quality education, strong currency, flourishing economy, good road networks, functional rail system, affordable healthcare service delivery and good life. All of which were legacies bequeathed by the departed colonial masters and early post-independence leaders. Now, sadly, everything has gone south in Nigeria accentuated by a self-serving rogue political elite, especially those of the last 20 years of our democratic rule.

I am of the strong view, however, that the current pathetic story of Nigeria that birthed what someone sarcastically called the “phone-pressing generation” who raged throughout the country protesting police brutality can be located between the failures of Soyinka’s “wasted generation” and the frustrations of Utomi’s “generation that left town”.

Soyinka’s generation were schooled in the best traditions and values of the country’s educational institutions provisioned by a most compassionate and contented ruling elite, driven as it were, by the ethos of people-centric service; most had free education up to the university level with multiple scholarship offers to boot; they were not made to spend more time at home than inside classrooms because their teachers were owed salaries and on perpetual strike (it’s claimed that between 1999 and now, university lecturers alone have gone on strike 15 times); upon graduation, they had the luxury of choosing from a cocktail of job offers made available to them at the convocation ground; those who took up scholarships to study overseas dashed back home upon graduation for a more assured and secure life, while those whose parents were public servants never experienced the scourge of arrears of unpaid salaries or withheld pensions. Above all, they never had to dread stepping out of their home for fear of being felled by the bullets of a murderous police unit that delight in “wasting” lives with impunity. There indeed was a country!

Utomi’s generation, as seemingly unfulfilling as Nigeria of their time was, admittedly “enjoyed that high quality education” but still walked away easily even when the value of the naira was higher than the dollar and almost at par with the pound. (The late economist and writer-activist, Henry Boyo, told me that upon completion of his Master’s degree overseas, he didn’t think twice before returning home because it was more rewarding). Ironically, they walked away even when the country had not unravelled as it has now.

The generation that raged this past week are the very ones that have been denied the very things their forebears took for granted. It only took the #EndSARS protests to trigger their long-bottled up fury against an underachieving Nigerian state. It was a rage at a country that has yielded itself to a buccaneering political elite that watched helplessly as poverty flourished and life became more “cruel, brutish and short” for its youth. Constituting over 54 per cent of the total 201 million population, according to the UNFPA, the Nigerian youth have been at the receiving end of everything that has gone awry with the country in recent years occasioned by leadership failure, crass corruption and bad governance. Educational and employment opportunities have increasingly withered away, only becoming the preserve of the privileged. In 2020, for instance, 1.9 million candidates registered for entrance examinations organised by the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board into 750,000 spaces in the country’s higher institutions. This means 1.2 million candidates will be left, frustratingly, to repeat the exam another year.

Even those who graduate do not have anything doing as persistent economic contraction has led to mass unemployment. All promises to diversify from oil-dependence have remained hot air, 60 years after. Data from the National Bureau of Statistics showed that Nigeria’s unemployment rate as of the second quarter of 2020 was 27.1% (about 21 million people) with 13.9 million currently unemployed while PricewaterhouseCoopers Nigeria, an audit and consulting firm, projects it will reach 28 per cent in Q3 2020 and 30 per cent by Q4 2020. The NBS reports that Nigeria’s youth population eligible to work is about 40 million, out of which only 14.7 million are fully employed. Put in context, the 13.9 million unemployed youth population is more than the population of Rwanda.

A 2018 study by the British Council warned that Nigeria was on the cusp of a demographic disaster if its bulging youth population were left without opportunities. The report cautions, “If Nigeria fails to plan for its next generation, it faces serious problems as a result of growing numbers of young people frustrated by a lack of jobs and opportunities. If these young people are healthy, well educated, and find productive employment, they could boost the country’s economy and reinvigorate it culturally and politically. If not, they could be a force for instability and social unrest.” This year, Nigeria was ranked the third most terrorised country in the world by the Global Terrorism Index, reeling from an intractable insurgency, banditry and terrorism.

The ongoing #ENDSARS protests merely presented an opportunity to ventilate the angst at a failed state. Government’s initial response suggested it either misread the situation or characteristically underestimated the bottled-up fury of the average Nigerian youth. A protesting young girl when asked in a viral video what the protest was about defiantly answered: “The protest is for our life (sic), it is for our future. We want SARS to end but that is just the beginning. They (ruling class) should just wait for us. We are not quiet anymore. They call us lazy youths, but we are not lazy. We just kept quiet. Now, we have woken up. We know what we are fighting for and we know what we want. We will not budge until we get what we want.”